INTRODUCTION

The bootloader is a very important part of embedded systems. It doesn’t always have to be present, but in most commercial embedded products it’s an essential component. Keep reading and I’ll explain why.

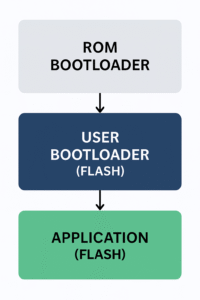

A bootloader is essentially an additional piece of firmware, separate from our main application that we program into the device through a programmer (for example via JTAG) to handle very specific tasks like mainly updating the system so we don’t have to rely on JTAG programming once the device is deployed in the field. It’s often said that it’s the first piece of code executed by the microcontroller, which isn’t entirely accurate.

What we (as users) typically flash is the User Bootloader. Meanwhile, the chip manufacturer usually preloads a ROM Bootloader into the ROM, responsible for low-level recovery and flashing through physical interfaces.

FUNCTIONALITIES

Back to the User Bootloader, its responsibilities are whatever we decide they should be. But in general, a bootloader must provide:

1. UPDATES

Our device needs a secure code section that lets us update the main application. Why is this important?

Imagine you decide to release a firmware update to fix a simple bug of a one-line change. You quickly prepare the update and distribute it to all customers. Shortly after, you start getting reports of a critical issue: devices are freezing completely. What the bootloader allows us to do is boot into a safe mode that has basic drivers implemented (USB, WiFi, BLE, CAN or SD-card…) so we can re-establish communication with the device, replace the crashing application, and update the new firmware.

If something like this happens and the device has no bootloader, then every unit might have to be returned for manual re-flashing. This would be a nightmare: High shipping costs, wasted time and lots of manual work. Remember that this type of failure can happen even if the update was tested before release.

2. VALIDATION

Another important aspect is validating the system. From a security perspective, we can add different levels of checks.

At the application level:

The main application can carry our signature, allowing us to verify that it was generated by us and flashed correctly. This can also be checked during the update process. It prevents unauthorized firmware to be executed in our device.

At the hardware level:

We can validate hardware components for different reasons: confirming the system is still functional (for example checking sensor registers to ensure communication is available), or making sure the microcontroller is still on the intended board and not extracted for malicious use. These validations can even influence the boot modes. For example, if some sensors fail but the device can still perform its main purpose, we can boot into a degraded mode.

3. SECURE DEVICE

Firmware updates involve sending update files. If these files aren’t encrypted, they become a security risk, someone could easily copy their functionality or extract sensitive information. That’s why update files should be encrypted, and the bootloader should implement the decryption logic so it can safely process and apply them.

Additional security measures may include version or date checks that prevent downgrading to outdated firmware critical for avoiding attacks where someone reflashes a vulnerable older version. We can also use eFuses to permanently lock down certain parts of the system.

DESIGN CONCERNS

These are key considerations when developing a bootloader. Once a device is deployed with its bootloader, it ideally should never need to change.

1. Memory layout definition

The memory map defines what gets stored in each section. This must be perfectly planned because once the device ships, it’s fixed. Make sure to leave as much space as possible for the main application, since its size tends to grow over time with updates.

Some developers reserve two equally sized firmware slots to implement a rollback mechanism. Each new update is written to one slot, ensuring there is always at least one valid firmware available in case the update fails or a bug is found.

2. Keep the firmware minimal but well audited

Don’t add unnecessary complexity. The bootloader should be as simple as possible while still doing what it needs to do. Simpler code is easier to test and less likely to contain bugs.

3. Optimize memory usage

Related to the previous point: avoid adding anything unnecessary. The smaller the code, the more memory available for the rest of the system.

4. Implement a secure and robust decryption method

Once deployed, the decryption mechanism cannot be changed, so choose something strong and not easily compromised.

5. Store keys securely

Consider using TPMs, cryptographic modules, or similar solutions to securely store keys used by the bootloader.

6. Check data from the main application

Even though the user bootloader doesn’t know the details of the application, having shared registers or markers is helpful, for example reboot counters, error flags, etc. These can help determine if the application is misbehaving, and whether the device should boot into the safe bootloader mode instead of the main firmware.

7. Deinitialize everything before jumping to the main application

This avoids conflicts with whatever the application needs to initialize.

HOW TO ENTER THE BOOTLOADER

The user bootloader should offer several ways to enter it. These mechanisms can be hardware-based or software-based.

For hardware entry:

A common method is using a microcontroller pin connected to something that trigger the bootloader mode. For example holding down a button during power-on.

For software entry:

We can use the register checks mentioned earlier to detect abnormal conditions. If the device isn’t running correctly, the bootloader can take over to provide a stable state for updating.

CONCLUSION

In this post I’ve highlighted what I consider the key aspects of developing a bootloader for microcontrollers: understanding what a bootloader really is and what it’s used for, as well as its key functionalities and main design concerns. I hope this helps when you are developing a bootloader for your embedded system.

What approaches have you used to implement bootloaders in your projects? Feel free to share your own experience with bootloader implementations in the comments.